Switzerland is famous for three things: chocolate, banking, and peace. But in November 1847, Switzerland was a war zone.

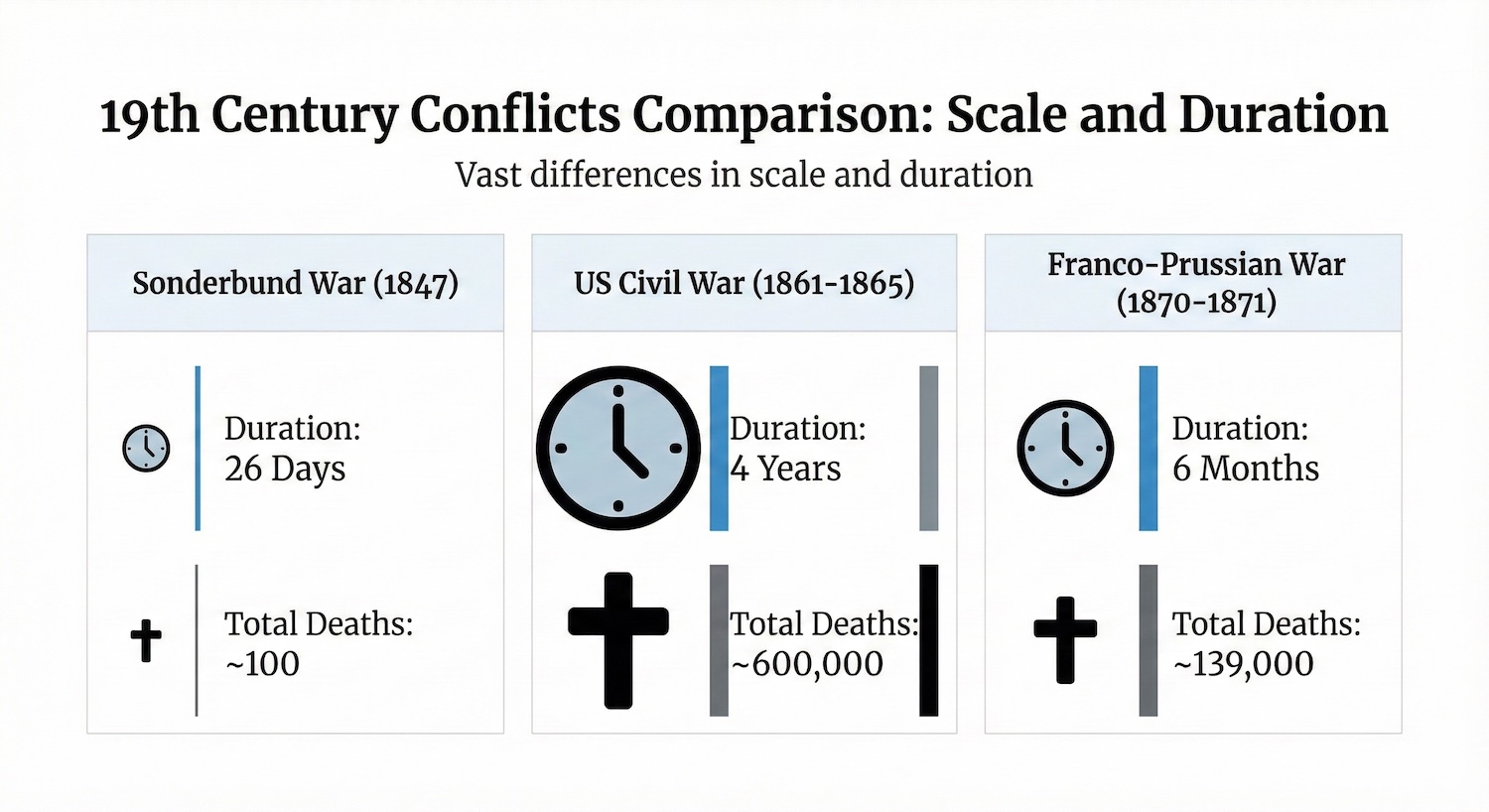

It sounds impossible. A civil war in a country the world thinks of as eternally neutral? Yes—and it lasted only 26 days. Fewer than 100 people died. Yet this short, strange war changed everything. It killed off the old confederation, created the federal state we know today, and proved that a country could wage war humanely while still winning decisively.

Without the Sonderbund War summary, modern Switzerland wouldn’t exist.

Quick Summary: What was the Sonderbund War?

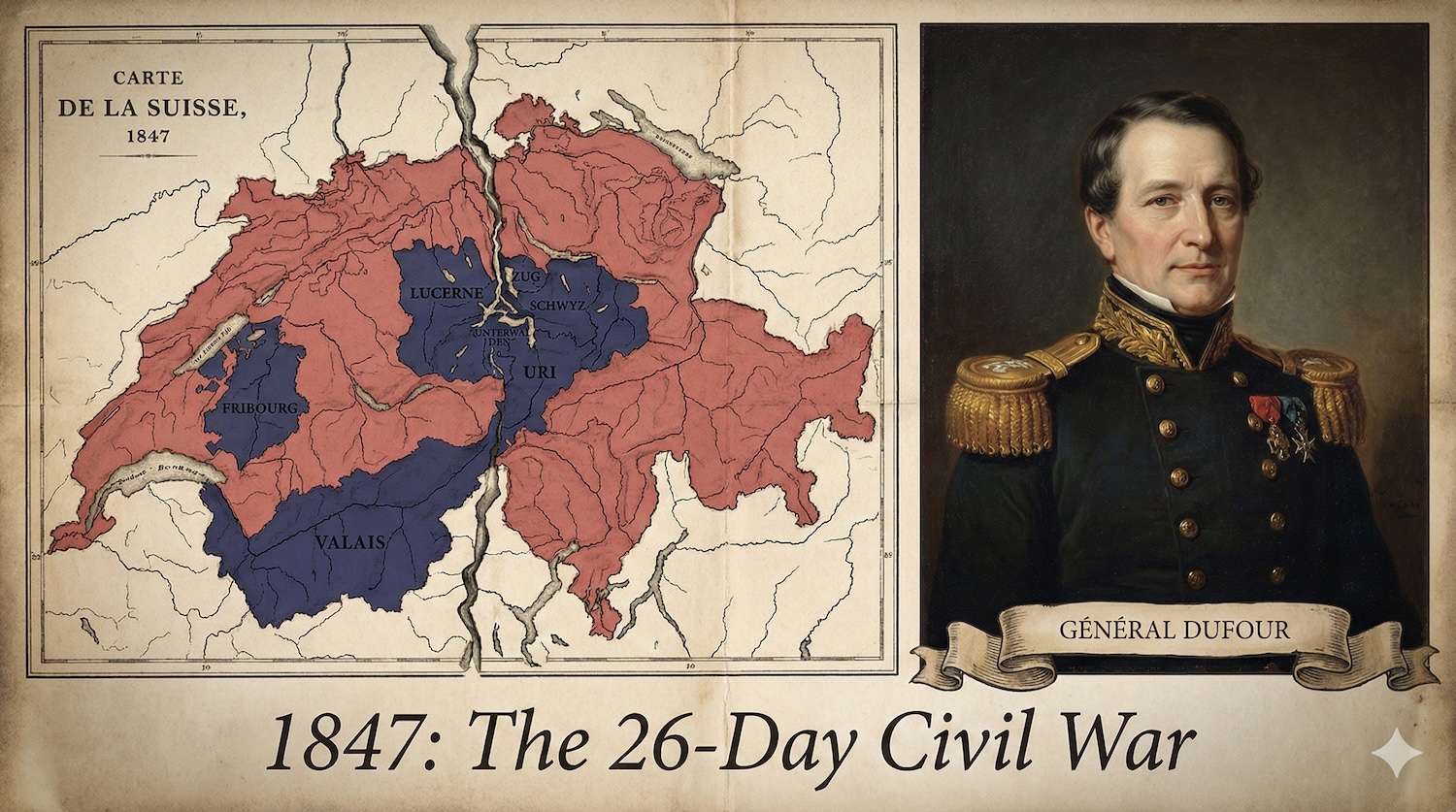

The Sonderbund War (November 1847) was a brief civil war in Switzerland between seven conservative Catholic cantons (the “Sonderbund”) and the liberal Federal Diet. The war lasted 26 days and caused fewer than 100 deaths. General Guillaume-Henri Dufour led the federal army of 100,000 and defeated the rebel forces decisively. The victory directly produced the Swiss Federal Constitution of September 12, 1848—the document that transformed Switzerland from a loose alliance of cantons into a modern federal state with a central government, national currency, and unified military.

Why the “Peaceful” Swiss Went to War

To understand why Switzerland fought a civil war, you need to see the deep fault lines running beneath its peaceful surface.

By the 1840s, Switzerland was split in two. On one side were the liberal, Protestant cantons—largely urban, industrial, and pushing for centralization. They wanted a strong federal government that could control education, regulate the church, and modernize the country. On the other side were the conservative, Catholic cantons—rural, traditional, and fiercely protective of cantonal independence. They feared losing their sovereignty to a central power.

The trigger wasn’t abstract philosophy. It was religion and education.

In 1841, the liberal canton of Aargau did something radical: it closed Catholic monasteries and convents. For conservative Catholics across Switzerland, this was a declaration of war. The liberals weren’t just passing different laws—they were attacking the church itself. If this could happen in Aargau, it could happen anywhere.

Then came the Jesuits.

The Religious Divide: Catholics vs. Liberals

The Jesuits had been expelled from Switzerland during the Napoleonic era. In 1844, the newly conservative government of Lucerne invited them back—not just as priests, but as educators. They would teach in Catholic schools and shape the minds of the next generation.

For liberals across Switzerland, this was an invasion. The Jesuits symbolized everything they feared: Catholic political power, education controlled by the church, and resistance to rational, secular progress. Bands of radical volunteers—called Freischärler—from neighboring liberal cantons crossed the border to fight them. These armed incursions failed but hardened both sides.

By 1845, the conservatives had decided they could not defend their values within the existing Swiss system. Seven cantons formed a secret military alliance called the Sonderbund (meaning “separate alliance”)—a pact that technically violated the 1815 Swiss treaty.

The Sonderbund Alliance Explained

The seven rebel cantons were:

- Lucerne (the epicenter—where the Jesuits were)

- Fribourg

- Valais (Wallis)

- Uri

- Schwyz

- Unterwalden (split into Obwalden and Nidwalden)

- Zug

These were the strongholds of Catholic traditionalism, all convinced that their way of life was under attack. Their goal was mutual defense: if the federal government tried to suppress them, they would defend each other.

But they weren’t alone. Even Ticino and Solothurn—both Catholic cantons—refused to join. They sided with the liberals instead. This detail is crucial: it wasn’t a simple Catholic-vs-Protestant war. It was a war about the future of Switzerland—whether it would be centralized or fragmented, liberal or conservative, modern or traditional.

Enter General Dufour: The Man Who Refused to Hate

In October 1847, Switzerland appointed a man who would change how the world thought about military leadership.

General Guillaume-Henri Dufour was 60 years old. He had spent his life in service: first to Napoleon, then to the Swiss military as an engineer and educator. He was a topographer who mapped Switzerland and a mathematical mind who designed fortifications. But he was also something rarer—a man who believed that military victory didn’t require hatred.

The Federal Diet handed him command of 100,000 soldiers. The Sonderbund had 80,000 to 84,000.

Dufour’s strategy was unconventional. Instead of preparing for a prolonged siege or retaliatory occupation, he prepared for speed. He wanted to end this war fast—before the great European powers could intervene. Austria, Russia, and France were all watching. If Switzerland became a battlefield for the ideological conflict between liberals and conservatives sweeping Europe, foreign armies could march in and end Swiss independence.

But Dufour had another conviction. He issued orders to his officers that sound almost modern:

“If a body of enemy troops is repulsed, give to the wounded the same care as you give to our own men. Treat them with all the forbearance due to one who is stricken. Disarm the prisoners, but refrain from any hurt and from reproach.”

And then, on November 5, 1847, he made a proclamation to his entire army:

“Soldiers, you must leave this battle not only victorious but also above all reproach. People should say of you: They won, but they did not hate.”

This was a general ordering an army not to seek revenge. It should have sounded naive. Instead, it changed history.

The 26-Day Campaign: How the War Was Won

The Sonderbund War began on November 3, 1847, and it began badly for the rebels.

The first action was a Sonderbund attack on Ticino, a Catholic canton that had chosen the liberal side. The assault failed immediately. The Sonderbund soldiers, moving across unfamiliar terrain, were repelled quickly. They had lost the initiative.

Dufour’s federal forces moved fast. Columns marched into the mountains of Uri, Schwyz, and the valleys of the Catholic cantons. The rebels couldn’t mass for a decisive defense. They were spread across difficult alpine terrain.

The key battles came in rapid succession.

On November 7, federal forces clashed with Sonderbund defenders at Lunnern. Another engagement at Geltwil followed on November 12. These weren’t massacres—they were professional military engagements where the side with superior numbers and discipline won. But Dufour enforced his orders: prisoners were not executed. Wounded enemies received care.

The Sonderbund hoped to hold Lucerne, the heart of the rebellion. The city sits on a plateau, defensible if properly garrisoned. But the federal forces were moving too fast, and Lucerne was surrounded.

On November 23, 1847, the decisive engagement took place at the Bridge of Gisikon, just outside Lucerne. The Sonderbund commander, Johann Ulrich von Salis-Soglio, had massed 20,000 soldiers inside the city and positioned his best troops near the bridge with artillery support. It was a strong defensive position.

The battle lasted six hours. It was the hardest fighting of the war. But Dufour’s superior numbers and organization prevailed. The Sonderbund forces were broken. With the city surrounded and escape impossible, Lucerne surrendered on November 24.

After that, the war collapsed. The remaining cantons, seeing Lucerne’s defeat, surrendered without further armed resistance. By November 29, even remote Valais capitulated. The war was over.

The “Miracle” Peace: Why There Was No Revenge

Here’s what didn’t happen after the Sonderbund War: there were no mass executions, no forced exiles, and no dismantling of Lucerne’s government. The victors didn’t install an occupying army to extract tribute or humiliate the losers.

This was extraordinary. In the 19th century, when civil wars ended, the victors typically punished the vanquished severely. The American Civil War, which would erupt 14 years later, would kill 600,000 people. European civil conflicts were vicious and vindictive.

But Dufour had kept his word. His soldiers had won without revenge.

Consequently, Switzerland healed remarkably fast. The Catholic cantons, defeated and humiliated, weren’t destroyed. They could still participate in building the new Switzerland. They had lost the political battle, but they weren’t erased from the nation.

Sonderbund War vs. Other 19th Century Conflicts: The “Bloodless” Civil War

This restraint—this refusal to hate—made reconciliation possible. Without it, Switzerland might have fractured into permanent hostile regions. Instead, it became unified.

The Birth of the 1848 Constitution

The Sonderbund War was barely over when Switzerland took its next revolutionary step.

On September 12, 1848, the Federal Diet promulgated a new Federal Constitution. This document didn’t just end the war—it transformed Switzerland’s entire political structure.

Under the old system, Switzerland was a confederation of nearly independent cantons bound by treaties. There was no central government, no national currency, no unified military (until Dufour created one for the war). Each canton jealously guarded its sovereignty.

The 1848 Constitution changed all that. It created:

- A Federal Government with real power over commerce, defense, and law

- A National Assembly with two chambers: the National Council and the Council of States (inspired by the US Constitution)

- A Federal Court to interpret the constitution

- The Swiss Franc, a unified national currency

- A standardized Swiss flag

- The principle of subsidiarity: cantons remain autonomous except where the federal constitution restricts them

The constitution also introduced male-only suffrage—giving all adult men the right to vote (though, as you’ll read elsewhere, women would wait over a century for that right).

So the Sonderbund War did something paradoxical: it was fought to defend cantonal independence, but it resulted in the loss of that independence. The Catholic cantons lost their struggle to remain isolated and sovereign. But in defeat, they became part of something larger—a modern federal state that would eventually become one of the world’s most stable democracies.

This is why some historians call the Sonderbund War “the war that created modern Switzerland.”

The war also triggered the expulsion of the Jesuits from Switzerland. In December 1847, the new federal majority ordered them out. The very thing the Catholic cantons had fought to defend was now forbidden. Yet even this didn’t produce lasting bitterness. The Jesuits were gone, but the Catholic cantons survived, adapted, and found their place in the new federal system.

Internal Link Note: The 1848 Constitution established male-only voting rights in Switzerland. Women wouldn’t gain the federal right to vote until 1971—over 120 years later. Read more about this extraordinary delay in our companion article on the struggle for women’s suffrage.

The European Powers Nearly Intervened

While Dufour was commanding his swift campaign, something crucial was happening in Vienna, London, and other European capitals: powerful men were arguing about whether to invade Switzerland.

Prince Klemens von Metternich, the Austrian Foreign Minister and architect of European conservatism, wanted to send Austrian troops to help the Catholic cantons. He feared what a liberal victory in Switzerland would mean for Europe. If Switzerland could crush conservative Catholics, maybe other liberals across Europe would grow bold. To Metternich, this war was ideological—a test of whether liberal radicalism could be contained.

France, also a Catholic power, considered intervention too. Even the Vatican bankrolled the Catholic cantons financially, hoping to help them resist.

But Dufour had calculated correctly. British Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston opposed any intervention. The British, while diplomatic about it, sent a mediator to Switzerland but made clear they would not stand by while Austria or France invaded. The 1815 Vienna Treaty allowed the great powers to intervene in Swiss affairs—but only if they all agreed. Palmerston’s opposition made unified intervention impossible.

More importantly, events elsewhere in Europe distracted the great powers. The revolutions of 1848 were brewing across the continent. Metternich and Palmerston had bigger crises to handle. The window for foreign military intervention closed before it could open.

Dufour’s speed—winning the war in 26 days—meant that by the time the great powers might have organized a response, Switzerland was already moving forward with its new constitution. The moment for intervention had passed.

From War to Red Cross: Dufour’s Unexpected Legacy

After the Sonderbund War, General Dufour lived another 28 years. But the war wasn’t his greatest achievement; it was only the beginning.

Because Dufour had treated enemy wounded with respect, because he had issued orders to care for the injured and spare the defenseless, he had done something revolutionary. He had shown that modern warfare could be humane.

In 1859, a young Genevan businessman named Henri Dunant traveled to Italy and witnessed the horror of the Battle of Solferino. Tens of thousands of wounded lay dying on the battlefield with no one to care for them. Dunant was so moved that he spent the next four years writing a book called A Memory of Solferino, which called for the creation of neutral relief organizations to care for wounded soldiers regardless of which side they fought for.

In 1863, Dunant brought his idea to Geneva. He gathered with four other citizens—including the now-retired General Dufour, then 76 years old. Together, they founded the International Committee for Relief to Wounded Soldiers.

This organization became the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). It grew into the world’s most powerful humanitarian organization, present in every major conflict since, saving millions of lives based on the principle that Dufour had practiced in 1847: that enemies deserve care, that violence should be minimized, and that humanity should be preserved even in war.

So the Sonderbund War, which seemed to many at the time to be a brutal civil conflict, became part of the story of one of humanity’s greatest achievements.

Common Myths About the Swiss Civil War

Myth #1: “The Sonderbund War was purely about religion.”

False. Religion was the flashpoint, but the deeper issue was political power. The Catholic cantons feared losing their sovereignty to a centralized state controlled by Protestants. The liberals feared that Catholics, empowered by the Jesuits, would resist modernization. It was about whether Switzerland would be one country or many—whether it would modernize or remain traditional. Religion was the vehicle, but power was the engine.

Myth #2: “Switzerland has always been peaceful.”

False again. The Sonderbund War was Switzerland’s last armed conflict, but it wasn’t the first. Before it, Switzerland had internal conflicts. The war is famous for how quickly it ended and how few died—but saying Switzerland “has always been peaceful” erases this violence and ignores the conditions that made the war possible.

Myth #3: “The Sonderbund cantons were purely defensive.”

Mostly false. While the Sonderbund was formed to defend against liberal encroachment, the Catholic cantons also acted aggressively—inviting the Jesuits back, resisting federal initiatives, and eventually declaring their alliance unconstitutional. Both sides contributed to escalation.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Sonderbund War

Sources & References

- Wikipedia: Sonderbund War

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonderbund_War - Wikipedia: Swiss Federal Constitution

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swiss_Federal_Constitution - Britannica: Guillaume-Henri Dufour

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Guillaume-Henri-Dufour - Wikipedia: Guillaume-Henri Dufour

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guillaume_Henri_Dufour - Wikipedia: Switzerland as a Federal State

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Switzerland_as_a_federal_state - MySwitzerland.com: “The Restoration and Sonderbund War”

https://www.myswitzerland.com/en-ch/planning/about-switzerland/history-of-switzerland/the-restoration-and-sonderbund-war/ - Swiss Spectator: “The Sonderbund War That Brought Peace”

https://www.swiss-spectator.ch/en/nederlands-de-sonderbundsoorlog-die-vrede-stichtte/ - International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC): “Guillaume-Henri Dufour — A Man of Peace”

https://international-review.icrc.org/sites/default/files/S0020860400023263a.pdf - Swiss National Museum Blog: “How the Revolution of 1848 Enabled the Geneva Conventions”

https://schweizermonat.ch/how-the-revolution-of-1848-enabled-the-geneva-conventions/ - EBSCO: “Swiss Confederation”

https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/swiss-confederation - University of Lucerne: “The Sonderbund War – the Last Armed Conflict on Swiss Soil”

https://www.zeit-fragen.ch/en/archives/2018/no-1-10-january-2018/the-sonderbund-war-the-last-armed-conflict-on-swiss-soil - Swiss State Secretariat (BAK): “The Swiss State and Its Citizens After 1848”

https://www.bar.admin.ch/bar/en/home/research/research-tips/topics/die-moderne-schweiz/schweizer-staat-und-volk-nach-1848.html - Swiss Military (VTG): “Guillaume Henri Dufour (1787–1875)”

https://www.vtg.admin.ch/en/guillaume-henri-dufour-1787–1875 - Red Cross History: “The Humanitarian Trail of the Red Cross”

https://shd.ch/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/The-humanitarian-Trail_cicr_les_sentiers_humanitaires_brochure_en_validation_1.pdf - Manresa-SJ.org: “Jesuits in Switzerland”

https://www.manresa-sj.org/stamps/2_Switzerland.htm

Asel Mamytova is a Swiss entrepreneur, cultural historian, and founder of Swiss Heritage—a platform dedicated to uncovering the untold stories of Switzerland’s past. A passionate advocate for Swiss history and culture, Asel combines rigorous research with engaging storytelling to make Switzerland’s complex heritage accessible to a global audience. Based in Switzerland, she explores the intersection of history, architecture, and national identity through her writing and projects.