You’re hiking near Lake Geneva on a beautiful afternoon. The Alps shimmer in the distance. Everything is Switzerland-postcard perfect.

Then you spot it: a charming pink house, nestled against the green hillside. The windows have white-trimmed shutters. Terracotta roof tiles. A mailbox by the front door. It looks exactly like the kind of chalet a wealthy Genevan might rent for the summer.

You get closer.

The windows don’t reflect light—they’re painted on solid concrete. The “wooden” shutters are molded stone. And that garage door? It swings open to reveal not a car, but two massive anti-tank cannons pointing directly at you.

Welcome to the Villa Rose, one of Switzerland’s best-kept secrets for 65 years.

The story of Swiss camouflage bunkers is a story about deception, paranoia, and art serving survival. During World War II, Switzerland didn’t just prepare to defend itself from Nazi invasion. It hired theater set designers to create an elaborate national illusion—turning concrete fortifications into picture-perfect chalets that would fool enemy pilots at 20 meters’ distance.

And it almost worked. Because Nazi Germany never invaded, these fake houses were never tested in combat. But they stand today as monuments to an extraordinary moment when architecture became weaponry, and when artists became soldiers.

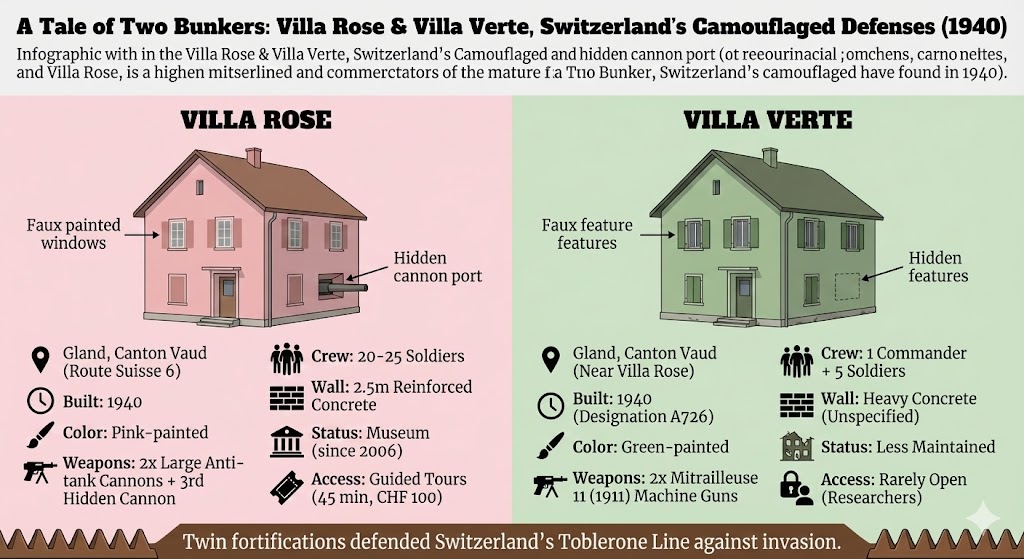

Swiss Camouflage Bunkers (Fake Chalets): Between 1940-1941, Switzerland constructed approximately 250+ fortified bunkers disguised as residential chalets and farm buildings as part of the “Promenthouse Line” (officially) or “Toblerone Line” (popularly). The two most famous are Villa Rose (pink, Gland) and Villa Verte (green, Gland), both designed as 2-story homes but containing 2.5-meter-thick concrete walls, hidden artillery, and machine gun emplacements. Swiss authorities hired theater set designers to create realistic window shutters, wood grain details, and painted windows to deceive at minimum 20-meter distance. The defensive line consisted of 12 fortresses linked by 2,700 anti-tank obstacles (“dragon’s teeth”). Villa Rose opened as a museum in 2006; the Toblerone hiking trail now follows the 17-km defensive line.

Switzerland’s Existential Crisis: Surrounded and Vulnerable

When Nazi Germany began its conquest of Europe in 1939, Switzerland faced an existential problem. The country was surrounded. Italy sat to the south. Nazi-occupied France surrounded Geneva to the west. The mountains offered some protection, but not from aerial bombardment or a coordinated invasion across the western border.

Switzerland’s government knew it couldn’t win a conventional military war against Germany. So they adopted a different strategy: delay and deception. Build defensive lines that would slow an invasion long enough to retreat into the Alps, where the terrain favored the defending army.

The Counterintuitive Solution: Hide the Fortress in Plain Sight

The problem was simple: how do you hide a military fortress in a landscape that tourists come to see?

The answer was counterintuitive: make it a house.

Starting in 1940, the Swiss army hired something extraordinary: theater set designers and professional artists. These weren’t architects or military engineers (though they had those too). They were the people who built illusions for stage productions—craftspeople who understood how to deceive the human eye through paint, perspective, and material manipulation.

The Art of Deception: Mastering Light, Shadow, and Detail

Their task was specific: make the bunkers look like local chalets when viewed from enemy aircraft or from the ground at a distance of 20 meters or more. Realistic window shutters became essential, as did wood grain details painted onto concrete. But the real challenge lay in mastering light and shadow. The designers had to calculate where the sun would be at different times of year, predict how shadows would fall across the concrete walls, and determine which angles would make painted details appear three-dimensional rather than flat.

Consequently, Swiss military fortifications got makeovers like film sets. The concrete walls were painted in pastel colors—pink, green, cream—matching the aesthetic of the surrounding countryside. False windows were painted directly onto the walls. Roof tiles were molded from concrete and painted terracotta. Gutters and downspouts were carefully detailed.

From the air, these bunkers looked like vacation homes.

But from inside, they were fortresses.

The Toblerone Line: Teeth of War

Run your eyes along the map from the Jura Mountains down to Lake Geneva. Between 1937 and 1941, Swiss engineers built something unprecedented: a 17-kilometer defensive line made of 2,700 concrete anti-tank obstacles and 12 fortified positions.

The obstacles became famous because of their shape: blocky, triangular, staggered. To locals, they looked exactly like the Toblerone chocolate bar. The nickname stuck so thoroughly that today, the entire line is officially called the Toblerone Line (formally, the Ligne fortifiée de la Promenthouse, named after the river that runs through the valley).

Each concrete “tooth” weighs 16 tons. They stand roughly one to two meters tall, arranged so tightly that a tank cannot drive between them. A vehicle that hits one gets stuck. Behind these obstacles lay minefields, barbed wire, and pillboxes where machine gunners could rake an invading force with crossfire.

The line wasn’t meant to stop tanks permanently. It was meant to slow them down—to give the Swiss army time to fall back into the Alps, where the terrain favored defenders. It was a defense strategy based on friction and time, not annihilation.

But the line itself had a bigger purpose: psychological. It announced to Germany: We are prepared. Invasion will cost you. It is not worth it.

Villa Rose & Villa Verte: The Famous Pair

Villa Rose vs. Villa Verte: Switzerland’s Twin Camouflaged Fortifications

The most iconic fortifications along the Toblerone Line are two houses built in 1940 in Gland, a town just east of Geneva. They sit only a few hundred meters apart, designed to provide mutual defensive support through crossfire.

Villa Rose looks like a pink suburban home. Two stories. Painted shutters. The kind of place a wealthy Genevan executive might escape to for weekends. Inside the concrete shell, 20-25 soldiers could operate 2 large anti-tank cannons and additional machine gun positions. The walls are 2.5 meters (over 8 feet) of reinforced concrete.

Here’s where the deception becomes masterful: the main garage door opens to reveal the cannon ports. The third cannon is hidden behind painted window shutters on the ground floor—so cunningly disguised that even today, visitors struggle to spot it without being told.

Villa Verte, painted green, sits nearby. It was designed to house machine gun nests and provide mutual support. Smaller garrison (1 commander, 5 soldiers), but equally lethal. The two houses would have created a killing zone—any tank moving through the valley would face fire from both sides simultaneously.

Here’s the historical irony: Germany never invaded Switzerland. These fortifications were never tested. The bunkers spent WWII in full readiness, fully armed, fully staffed, waiting for an invasion that never came. And then the Cold War began, and the bunkers sat through 80 more years of peace, slowly decaying as technology made them obsolete.

Until 2004, when photographer Christian Schwager published a book called Falsche Chalets (Fake Chalets), the existence of these bunkers was a military secret. Schwager had documented over 100 of them, and estimated at least 250 more existed across Switzerland, each one a hidden weapon disguised as a house.

Why Theaters Hired Theater People

The moment you understand why Switzerland hired theater set designers, you understand how seriously they took this camouflage project.

Theater designers understand illusion. They know that a convincing deception isn’t about perfect realism—it’s about the right details at the right distance. In a stage production, you don’t need every element to be anatomically correct. You need the elements your audience will actually see to be convincing enough to hold the illusion.

The same principle applies to camouflage.

A painted window doesn’t need to be a perfect reproduction of a real window—just convincing enough from 20 meters away. The illusion requires shadows positioned precisely, reflections of sky and surroundings captured in the paint, and that crucial three-dimensional quality that makes the brain surrender and accept it as real.

Swiss authorities understood this. They hired professionals who had spent careers manipulating human perception. These designers created trompe-l’œil (optical illusion) effects on concrete walls. They painted wood grain details with such precision that even today, close-up photographs sometimes fail to reveal them as paint.

This obsession with detail echoed Switzerland’s broader military philosophy. After the Sonderbund War in 1847, when the nation unified its defense under federal command, Switzerland learned that survival depended on meticulous preparation. Nearly a century later, that same commitment to precision manifested in these camouflage techniques—where every shadow, every painted detail, every calculated angle mattered.

The precision was extraordinary. Designers calculated the sun’s position at different seasons, understanding how shadows would fall across the concrete walls at different times of year. They wanted the shadows to look natural, not painted on.

Meanwhile, architects ensured the illusion didn’t interfere with actual military function. The bunkers had to be real fortresses—with thick walls, proper ventilation, command centers, storage for ammunition. The deception was a layer over military reality, not a replacement for it.

A Landscape of Secrets: Beyond Villa Rose

Villa Rose is the most famous, but the Toblerone Line contained 12 major fortifications. Many others scattered across Switzerland took on different disguises.

In the Alps, camouflaged bunkers were disguised as wooden barns—perfect mountain architecture that didn’t raise suspicion. A hiker passing a humble Alpine barn might not realize it contained artillery. The barn had a wooden facade, weathered appearance, authentic roof. Inside: concrete, cannons, soldiers in shifts waiting for an invasion that never came.

In rural areas, fortifications looked like simple wooden sheds. In cities, they took the form of suburban villas. The camouflage adapted to location—always matching the local vernacular.

Across Switzerland, historians now estimate there were at least 8,000 bunkers built, though only a fraction were disguised as “fake chalets.” Most were pure concrete structures, undecorated, undisguised. But the 250+ that received full architectural camouflage remain the most unsettling—and the most aesthetically interesting.

The Secret Stays Secret (Until 2004)

Here’s what’s remarkable: most Swiss citizens had no idea these bunkers existed.

The fortifications were classified as secret military installations until 1995. Even after that, few people paid attention. The bunkers looked like normal houses. If you lived next to one, you might have wondered why your neighbor never seemed to be home and strange soldiers occasionally appeared at all hours. But you probably didn’t investigate too closely.

It wasn’t until 2004—65 years after the Villa Rose was built—that Christian Schwager’s book made the bunkers public knowledge. Suddenly, the internet filled with images and discussions of the “fake chalets.” Architecture blogs picked up the story. Historians began documenting them seriously.

In 2006, Villa Rose was restored and opened as a museum, allowing the public inside for the first time. Today, visitors can see the recreation of 1940-era military equipment: the cannons, the machine guns, the command center. There’s even a famous detail—the grenade-throwing toilet, with a port in the wall where soldiers could throw grenades at attacking infantry attempting to storm the bunker.

Walking the Toblerone Trail: Tourism Meets History

You can visit the bunkers. In fact, the Swiss have made it remarkably easy.

In 1996, a preservation association began developing the “Sentier des Toblerones” (Toblerone Trail), a 17-kilometer hiking path that follows the entire Promenthouse defensive line from Bassins in the Jura down to the shores of Lake Geneva. The trail winds past the 2,700 anti-tank obstacles, past the preserved fortifications, past the reconstructed command bunkers.

The walk takes 4-5 hours at a comfortable pace. Yellow diamond waymarks guide you. At Villa Rose, you can stop for a 45-minute guided tour (minimum 5 people, about CHF 100 for a small group). You can even rent the soldier quarters on the first floor of Villa Rose for about CHF 300 per day—meaning you can sleep inside a camouflaged WWII fortress.

It’s one of the strangest tourist experiences Switzerland offers: a hike through a defense line built to repel invasion, now converted into a pleasant historical walking trail with cafés and souvenir stands.

The Legacy: Deception as Art

The Villa Rose and the Toblerone Line are museum pieces now. They’re preserved not because they saved Switzerland (they never had to), but because they represent something singular: a moment when military necessity, artistic creativity, and national paranoia created something genuinely strange and beautiful.

Theater designers created architecture that isn’t quite a building and isn’t quite a façade. It’s architecture as theater—as complete illusion. Walk past it casually, and you see a house. Study it carefully, and you see deception. Look at the details with expert knowledge, and you see the work of artists and engineers collaborating to create the perfect lie.

The bunkers are relics of Cold War thinking, of the era when Switzerland believed neutrality required total military preparedness. They’re also monuments to how seriously a small country took its survival. And they’re unexpected examples of art in service of war—where painters, set designers, and architects were drafted into creating illusions that might never be tested.

As photographer Christian Schwager noted when he first documented them: the Swiss took their architectural deception seriously. The fake chalets weren’t sloppy or obvious. They were meticulous, detailed, precise. They were built by people who understood that a good lie requires attention to every detail.

That obsession with detail—that’s very Swiss.

Frequently Asked Questions About Swiss Camouflage Bunkers

Sources & References

- Atlas Obscura: “Villa Rose – Switzerland”

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/villa-rose - Messy Nessy Chic: “Unmasking the Bunkers Disguised as Quaint Swiss Villas”

https://www.messynessychic.com/2015/06/26/fake-chalets-unmasking-the-bunkers-disguised-as-quaint-swiss-villas/ - 99% Invisible: “Designed for Demolition – Why the Swiss Rigged Critical Infrastructure to Explode”

https://99percentinvisible.org/article/designed-for-demolition-why-the-swiss-rigged-critical-infrastructure-to-explode/ - Wikipedia: “Toblerone Line”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toblerone_line - Sentier Historique La Côte: “Villas Rose et Verte”

https://www.sentierhistoriquelacote.ch/en/the-history-trail/villas-rose-et-verte/

Asel Mamytova is a Swiss entrepreneur, cultural historian, and founder of Swiss Heritage—a platform dedicated to uncovering the untold stories of Switzerland’s past. A passionate advocate for Swiss history and culture, Asel combines rigorous research with engaging storytelling to make Switzerland’s complex heritage accessible to a global audience. Based in Switzerland, she explores the intersection of history, architecture, and national identity through her writing and projects.